BY ALEC MACFARLANE

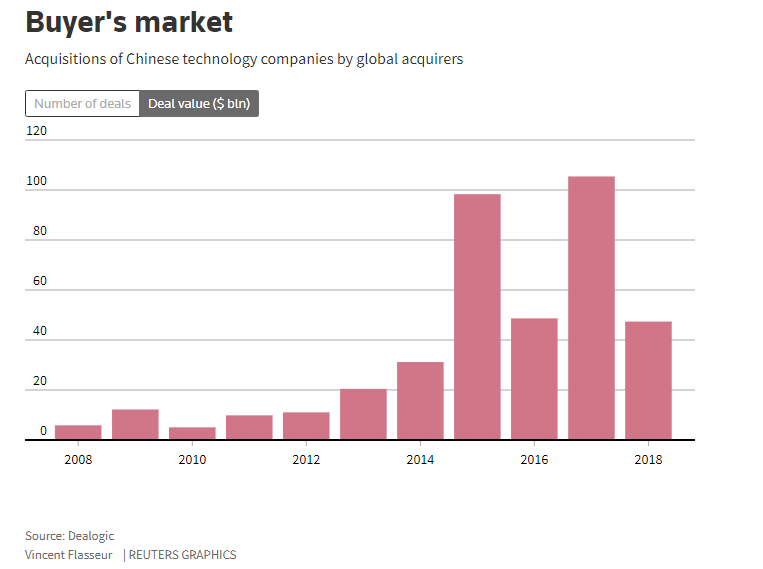

ByteDance would add some oomph to China’s BAT. The fast-growing creator of news and video apps is already privately valued at $75 billion, putting it on par with web search outfit Baidu, whose public equity in early December was worth some $65 billion. A 2019 merger between the two will modify the constituent parts of the acronym shared with Alibaba and Tencent.

Software engineer Zhang Yiming started ByteDance in 2012 with Toutiao, an app that uses artificial intelligence to deliver bespoke individual news feeds. When the company learned how Chinese youth love to share short video clips with each other, it developed TikTok, known locally as Douyin. The video services claim over 500 million monthly active users, creating fresh expectations that ByteDance can spot the next big thing and use its algorithms to design new market-leading apps.

Competition for online advertising is cutthroat in China, however. About 10 companies, including Tencent and web portal Sina , share most of a pie estimated by iResearch to be some $73 billion. Pressure will only increase as China’s economy cools. Marketing budgets are often among the first to be cut. Baidu is in particularly bad shape. Revenue growth is abating and efforts to diversify have been slow.

That makes a union of Baidu and ByteDance a tantalising prospect. Aside from the potential cost savings, Baidu would provide ByteDance with a stepping stone to business customers. The web group led by Robin Li also has some powerful artificial intelligence of its own to contribute. And it would give ByteDance, backed by Sequoia Capital, KKR and other investment firms, an easier path to capital markets, which have become increasingly difficult for new tech ventures to enter at the exuberant valuations they want.

For Li, owning a slug of the combined company would give him a stake in a bigger, more promising group. What’s more, both ByteDance and Baidu are among the few sizeable Chinese technology enterprises not funded by either Alibaba or Tencent. Together, they would prove a more formidable force. The challenge will be for two strong, rival personalities to see eye to eye. Such bountiful opportunities, though, suggest a double-B deal is meant to be.

First published Dec. 28, 2018.