BY GEORGE HAY AND LAUREN SILVA LAUGHLIN

Even by his own standards, Donald Trump has been contradictory on oil. The U.S. president spent much of 2018 berating the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries for keeping crude prices high by undersupplying the market. At the same time, he exacerbated the problem by reinstating export sanctions on Iran. An early December cut by OPEC and Russia is an irritant, but relatively low prices still look attainable.

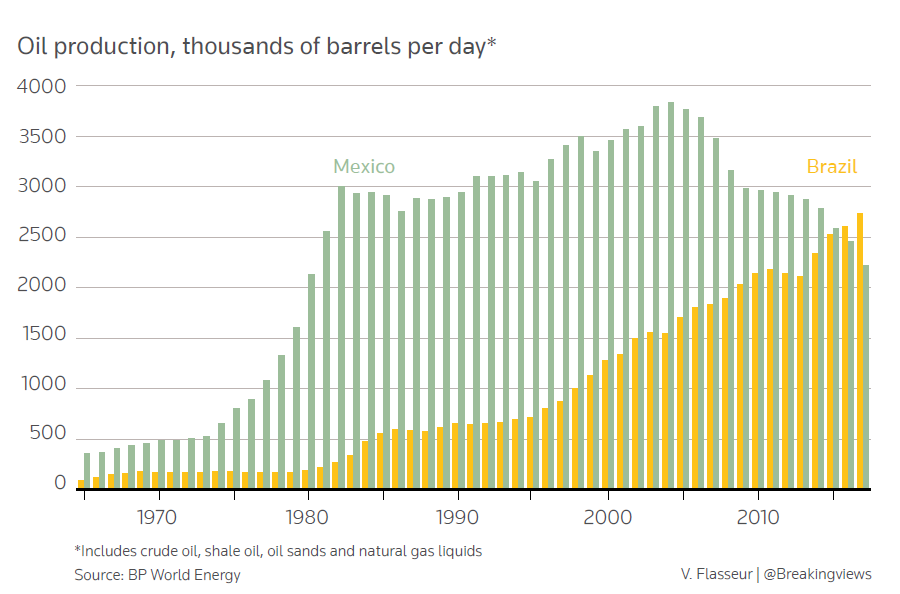

On current projections, the reduction of 1.2 million barrels per day removes much of a potential glut caused by epic pumping by Saudi Arabia, Russia and the United States, now a net oil exporter. Combining the International Energy Agency’s forecasts for oil demand in 2019 and its estimate for non-OPEC supply, the oil-producing bloc only needs to pump 31.6 million bpd to balance the market – 1.4 million below its October output.

Given Trump’s targeting of Iran’s 3 million barrels of daily production, the OPEC+, existing OPEC countries and others like Russia who are acting along with them, reduction is unhelpful. At worst, the combination could leave supply too tight, pushing prices up again.

Yet there are reasons the president can hope for a more favourable outcome. Demand growth could undercut IEA expectations – Wood Mackenzie estimates an increase of just 1.1 million bpd for 2019 while U.S crude production is seen jumping to 12 million bpd, up from 9.4 million a day in 2017. Most powerfully of all, Trump has greater scope to tell Saudi’s crown prince what to do.

The White House gave Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman a pass in November on whether he was involved in the murder of journalist Saudi Jamal Khashoggi. The president could use this leverage to call for an end to the 18-month-old blockade of Qatar or even of the war in Yemen, which the Brookings Institution says costs Saudi $50 billion annually.

But the most obvious power play involves oil, where Trump could insist MbS resist future OPEC+ cuts. That would make any potential squeeze temporary, and allow Trump scope to enforce sanctions against Tehran.

The fly in the ointment is U.S. Congress, which could yet override Trump and punish MbS and Saudi. To keep prices low as a 2020 election nears, that may necessitate keeping Iranian crude flowing by renewing waivers allowing big importers to continue. That would make Trump look inconsistent – something he appears to easily let roll.