BY SWAHA PATTANAIK

What’s the biggest threat to global markets in the coming year? It’s not a rise in U.S. interest rates, or the end of the European Central Bank’s bond buying. Rather, it’s the Bank of Japan. Even small adjustments by Governor Haruhiko Kuroda to ultra-loose monetary policy could agitate global asset prices more than other, widely expected changes.

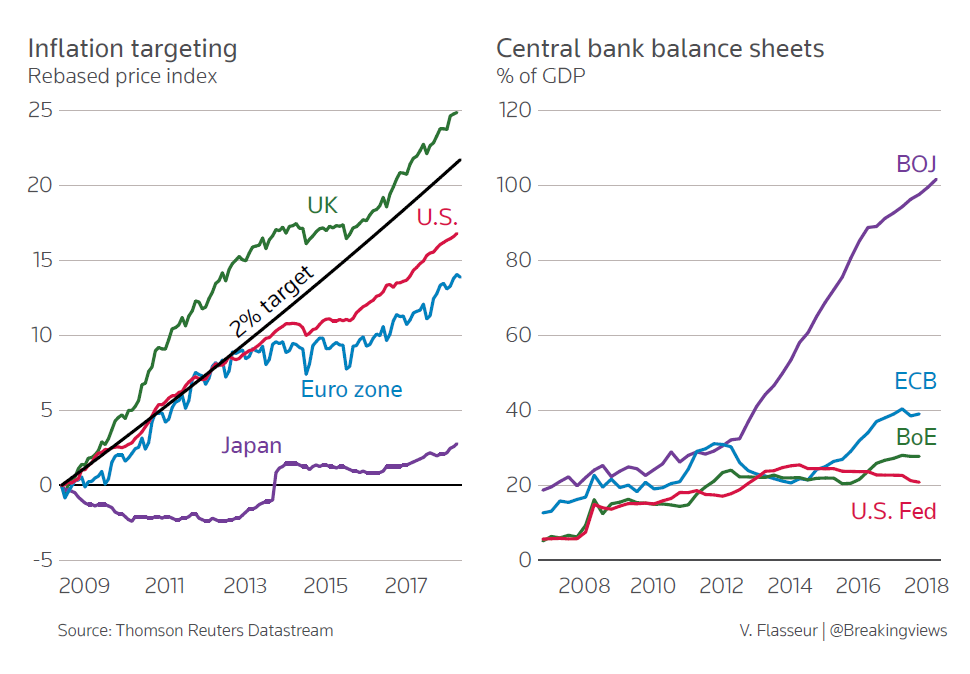

The BOJ already owns assets collectively worth more than the country’s entire GDP. Even so, it will keep growing its balance sheet after other major central banks have stopped. Any hints of a shift could alarm investors, whose assessments of risk and reward have been distorted by years of global central bank liquidity injections.

Reports in 2018 that the BOJ was debating scaling back stimulus triggered bond and currency volatility.

Kuroda is, in one sense, damned either way. Japan’s central bank is some distance from hitting its 2 percent inflation target. BOJ monetary policy is, however, aggravating the problems of regional banks. Roughly half of them have reported losses in the past two years or more on their lending business as the gap between what they pay for funding and what they get from making loans to customers has been squeezed.

If monetary policy risks doing more harm than good, the BOJ may be tempted to signal it’s willing to allow 10-year government bond yields to move in a wider range around zero or even raise short-term interest rates from minus 0.1 percent. Yields on Japanese government bonds would immediately jump. Nearly half are owned by the central bank and trading can be illiquid. Other markets will also feel the chill. Japanese investors have gone abroad to earn better returns, and will return if domestic yields rise enough. For example, Japanese investors bought about 4.7 trillion yen ($42 billion) of foreign currency bonds in September alone.

French and Spanish government debt, as well as U.S. credit, have proved popular relative to the size of the markets and could therefore face outsize hits. Currency hedging costs have risen so Japanese investors may bail out of overseas assets instead of paying for expensive protection. Those who have left their exposure unhedged to avoid paying for such insurance will be even quicker to do so.

Doubtless, U.S. Federal Reserve chief Jerome Powell, who is likely to keep raising rates throughout 2019, carries a big stick. But his actions are widely trailed already. That’s why Kuroda has the greater potential to jangle the market’s nerves.

First published Dec. 24, 2018.